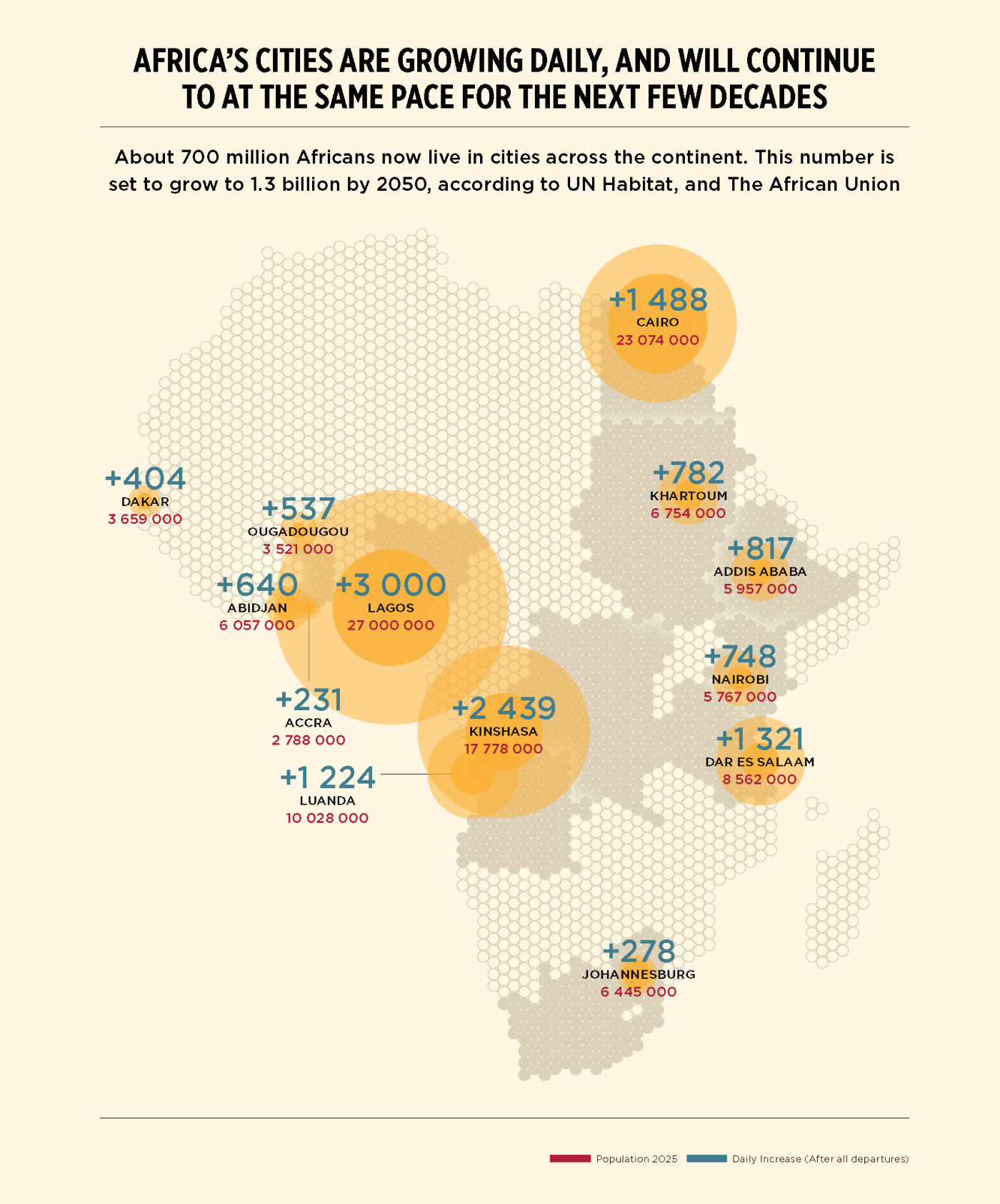

Here’s the reality we’re facing. By 2063, a billion more Africans will be living in cities than today. Right now, 23 of Africa’s 52 countries are classified as low-income, and more than 80% of urban jobs are informal—a figure that’s barely better in middle-income countries.

If you are in that 80%, chances are you’re stuck in a lifetime of piecemeal work that makes it almost impossible to secure decent housing, or access to basic services like water, sanitation, and electricity. That’s before you’ve thought about paying the rent on time, or covering your bills. Getting a mortgage on your own place some day? A pipedream. Makeshift work inevitably leads to a kind of makeshift life, or “slum living” as the UN calls it.

Young people in most African cities are growing up in these conditions, which makes the idea of finishing school, or going on to vocational or tertiary training, and ultimately finding a stable job, seem impossible. And that’s if there are any stable jobs.

But here’s the more insidious part: living in slums doesn’t just limit opportunities—it crushes hope. As anthropologist Arjun Appadurai puts it, slums make it nearly impossible to develop “the capacity to aspire”. When your daily reality is survival, dreaming about a brighter future feels pointless. The here and now is the only thing.

There’s been a lot of talk about the “resilience” and “inventiveness” of African youth—their tech fluency, their willingness to take on corrupt political elites, as seen in recent protests in Nairobi, Maputo, and Dakar. But what good are those qualities when you’re dealing with unreliable electricity, limited access to decent schools and healthcare, and virtually no platforms or political expression? Throw climate change into the mix, and we’re looking at a future that’s unpredictable at best, catastrophic at worst.

Scientists estimate that 70% of African cities are extremely vulnerable to climate change, and it’s always the poorest who get hit hardest. People in slums often lose everything to floods because they have no choice but to build with cheap materials in flood-prone areas and on unstable slopes. Without insurance—because who would insure them?—they live under the constant threat of losing everything and starting over. For city governments, it’s easier and cheaper—in the short term—to react to disasters than to invest in prevention. But this reactive approach traps them in an endless cycle of emergency response, exacerbated by the increasing severity of climate events. Rinse and repeat, with no way out.

Most African city governments understand these dynamics perfectly well, but lack the legal authority and funding to build the capabilities they need for effective urban planning. Many national governments talk a good game about devolving power to cities, but few actually do it. The African Union adopted a charter on decentralisation in 2014, but only eight member states have ratified it so far. South Africa was the last to sign on in 2022, and we still need 15 countries for it to take effect. Where’s the urgency? Where’s the leadership pushing this forward?

The slow progress toward democratic devolution has many causes, but the biggest one is political fear. Since multiparty democracy emerged in the early 1990s, opposition parties have consistently found their strongest support in slum populations. This terrifies the aging political class—many of whom trace their legitimacy back to liberation movements—and has seriously damaged the development of the continent’s cities.

To understand how we got here, we need to look back over the past half a century.

When African states gained independence in the 1960s and 70s, most cities shared a common structure: a modern core that mimicked European cities, serving as the political and commercial hub for colonists, physically separated from areas designated for indigenous populations.

Even within the colonial areas, there was clear class stratification. The least educated workers, holding the most menial jobs, lived farthest from the white colonial core. Those in clerical and service jobs—clerks, teachers, bus drivers, police officers—lived in townships closer to the center, but still with far less access to services and amenities.

After independence, new urban investments didn’t just maintain this colonial spatial arrangement—they made it worse.

The newly liberated native middle class didn’t just take over running the state from departing colonists. Many used their political power to carve out commercial interests for their parties, themselves, and their families in the neocolonial economy. This recreated the same skewed investment patterns, creating comfortable middle-class enclaves surrounded by expanding makeshift neighborhoods as more people moved to cities seeking opportunities. Chronic underinvestment in these growing areas created the conditions for systemic poverty and exclusion—the slums that define African cities today.

“”

Following colonial logic, it was considered politically essential to prioritise agriculture. After all, the thinking went, Africans were naturally connected to the land.

Investment in these new slums was seen as unnecessary. Following colonial logic, it was considered politically essential to prioritise agriculture. After all, the thinking went, Africans were naturally connected to the land. In the 1960s, making Africa the world’s breadbasket seemed revolutionary. By definition, Africans weren’t urban subjects—urbanisation was somehow unnatural and contrary to indigenous culture.

The anti-colonial movements that gained independence by the 1960s were deeply rooted in agrarian ideas about freedom. Colonial violence meant land dispossession, so freedom meant returning land to its rightful indigenous owners—working it through agriculture and collective ownership. Traditional African values were tied to pre-colonial cosmologies that emphasised the connection between human and natural systems, expressed through rituals and celebrations centred on the soil.

This worldview shaped the first generation of post-colonial administrators, who focused on two priorities: making

agriculture and mining the backbone of the economy, and installing the new political class in the urban areas formerly occupied by colonial administrators as a symbol of political autonomy.

The economic focus on primary sectors perpetuated neocolonial dependence on Northern investors and markets. The indigenous elite became brokers who could accumulate modest capital but never gained equity or autonomy to develop indigenous businesses that could control raw materials and their processing. This is why African economies remain asymmetrically positioned in global value chains and why structural transformation has been so elusive. It’s also why Agenda 2063 promotes economic transformation within a single African market as the continent’s most important reform.

Since traditional leaders continued to play important roles in stabilising post-colonial politics, land-use regulations remained under traditional authorities. The complexity of these land tenure agreements made urban investment extremely difficult. Things got worse in the late 1970s and 80s when many African governments faced economic crises and increasingly relied on authoritarian rule.

The 1970s was a boom time for Africa. Cheap loans were readily available, and many states enjoyed a resource boom, with the rise of fossil fuel revenue for many states.

This petrodollar growth was short-lived and soon became a nightmare. Between 1979-80, interest rates skyrocketed due to oil price hikes after the Iranian revolution and Middle Eastern instability. The 1980s and much of the 1990s became a period of profound economic stagnation and impoverishment, coinciding with rapid population growth driven by higher fertility rates and successful vaccination programs that reduced infant mortality.

The Bretton Woods institutions stepped in with a single cure-all. Their medicine of choice was what came to be known as “structural adjustment”, a series of belt-tightening measures imposed on African countries if they wanted to receive loans from the IMF and the World Bank. Promoted as a remedy, it instead worsened the continent’s developmental crisis.

Africa lost two decades to structural adjustment, a period that coincided with accelerating urbanisation. Most states weren’t ready for this reality, and their lack of foresight continues to haunt the continent’s cities. Meaningful institutional reforms like those outlined in the African Charter on Decentralisation will remain stalled until political leaders see them as urgent—which means loosening their grip on power and becoming accountable to the slums and the growing population of frustrated young people.

“Resilience” can only take young people so far. They’re now directly challenging the rigid, unrepresentative political cultures that have become barriers to change rather than enablers of their “capacity to aspire”.

But all is not lost.

The future is still ahead of us. Rather than continuing to relitigate past failures, we need to prioritise spatially aware public policy and integrated infrastructure investment.

This isn’t just urgent. It’s essential.

The anti-urban policies that most post-independence governments adopted resulted in a lack of proactive city planning and serious spatial economic policies across the continent. Every African—not just young people!—needs to push back against the stubborn refusal to allow strong, empowered local governments that can work with citizens and businesses to create environments for dynamic cities. Cities that can generate not just traditional infrastructure, but new forms that enable residents to benefit from economic agglomeration, sustainable productivity, education, and innovation.

“”

To be blunt, few of the nearly 700 million Africans now living in the continent’s cities trust the institutions tasked with delivering the basics they need for a fair shot at economic and social mobility. Transforming these institutions and their cultures won’t happen organically.

A fit-for-purpose regulatory environment is fundamental. The AU’s ambitious Agenda 2063 aims to “reposition Africa in the world to effect equitable and people-centered social, economic and technological transformation and eradicate poverty”, fulfilling “our obligation to our children as an intergenerational compact”. It provides, if not a roadmap, at least a North Star for the continent and its cities.

The intergenerational compact that Agenda 2063 proclaims can only be fulfilled if it deliberately pursues sustainable urbanism as the cornerstone of pan-Africanism.

Looking ahead, four things become clear about how we can move forward.

As Africans, we need to develop a deep alternative imagination for overcoming the dysfunctional urbanisation that threatens our future.

This means reframing our affordable housing and infrastructure challenges and fostering innovation across policy, finance, design, and citizen participation—right down to how we build.

Given that two-thirds of Africa’s built environment has yet to be constructed, we must commit to local innovation that can seed ecosystems creating sustainable technologies and construction value chains around alternative building materials, integrating and updating promising indigenous knowledge.

We need to balance learning from what works elsewhere with developing alternatives suited to our contexts. The glitz and glass of high-tech modernism in Dubai, Shanghai, and Singapore isn’t the model we should be striving for.

Elsewhere in this Special Report, you’ll find arguments that our current governance, policy, planning, fiscal, and coordination mechanisms need a complete reboot. A more coordinated approach to these dimensions is crucial for creating the cities Africa needs to deliver on Agenda 2063’s intergenerational promise.

A commitment to radical transparency by African governments at all levels is non-negotiable. This means putting accountability at the heart of the institutional recalibration that contributors across these pages advocate for. As citizens, we need to demand an end to top-down decision-making, procurement manipulation, and bureaucratic inertia embedded in public administration cultures across most African governments.

To be blunt, few of the nearly 700 million Africans now living in the continent’s cities trust the institutions tasked with delivering the basics they need for a fair shot at economic and social mobility. Transforming these institutions and their cultures won’t happen organically. We need distributed leadership that demands investment in and cultivates purpose-driven innovation ecosystems where all key players—local universities, thinktanks, social movements, business interests, philanthropic actors, and every citizen—play a role and feel equally represented.

There are important green shoots of innovation emerging in cities across the continent. Rather than seeing them as outliers, we need systems that embrace and build upon them, creating learning networks that can weave them together into a coordinated whole with the momentum to accelerate effectiveness and impact.

This is a call to actively follow the North Star that can translate Agenda 2063’s vision of an intergenerational pact into an operating model for the African cities yet to come.

The people who will make up that extra billion are moving to Africa’s cities now. It’s unstoppable.

The clock is ticking.